On Petro-Propaganda and Being an Artist in ‘Alberta’

Part II

Part II of a three-part conversation with Christina Battle and Rita McKeough, two artists that participated in the first iteration of Remediation Room, guided by Remediation Room curator Alana Bartol. Visit Remedy Toxic Energies: Summoning Circle (by Christina Battle) and Center for Interspecies Mutual Support in Troubled Times (by Rita McKeough) to learn more about their artworks. Visit the Artworks and Artists sections of this website to view all of the artists and projects. Read Part I here.

Image: Christina Battle, postcards for a better budget: reimagining the cut – participatory project at Latitude 53 (Edmonton), curated by Noor Bhangu, 2019 & 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Image description: A collage with cut-out, black and white images of a bird with its beak open perched on a branch next to mushrooms. The background is filled with stripes and patches of bright colours. In the upper right corner, there are five cut-out individual words in black text on a white background that read “Albertans deserve better need better”.

Alana:

In certain ways, you've already touched on this, but I guess I just wanted to ask the question, how does living in so-called Alberta impact and shape your artwork?

Christina:

Since reading your prompt for this question earlier, I've been really stewing on it. I think, for me, it really shapes everything. I think even my interest in thinking about the environment as this broad, large thing really comes from having grown up in this place that has such a problematic relationship with land and resources and histories. And so I just feel like it's the thing that drives my politics and culture and everything about me. So it's incredibly important. And I think even when living elsewhere, I was really inspired by trying to take up some of these concerns in conversations and introduce them into other conversations in other regions.

I think there's something weirdly inspiring about having all of my important moments while growing up happen in a place that's actually so hostile to grow up in, and I don't know, is that weird to be grateful for that? I was just thinking about how - obviously, things are bad in Alberta now, and they always have been - it's been such an oppressive place for decades and decades, and there's something about that that fuels this insistence on trying to think about things in other ways that I don't know I'd have in the same way if I didn't have that constant screaming against the dominant norm my whole life. So thank you, Alberta, I guess.

Alana:

Yeah. <Laugh> we can all thank Alberta for being that horrible thing we're all trying to work against.

Christina:

I'm working on this project right now that's really thinking through air pollution, and I'm just really aware of how when I grew up here, I had really extreme asthma and lung problems, as did basically everyone I know. And as soon as I left, that all went away, and now that I'm back, I have these same issues again. I'm coughing all the time. I really respond to the air in a way that I'm much more aware of now, having left it for a while. All of these things about this place that are just so polluting and toxic that I think are just so normalized here. There's just something about that that’s hard to ignore, you know?

Rita:

I moved here in 2007, and before that, I'd done a lot of work when I was younger in Calgary as well, dealing with urban redevelopment and violence against women, and different things that were standing out to me that I needed to address. But it was when I moved back that I started working with issues affecting the environment. When I first came back, I was working with ideas of industrialized agriculture and the unacceptable level of care of animals in industrial food processing.

And then I was immediately taken to resource extraction because it's such a big part of the economy, but it's so complex and problematic. And again, the same as you, Christina, I think that it was so horrific and extreme that there was no way I couldn't address it, and it pushed me to be active about it and pushed me towards the research. And, again, in a funny way, you know, it steered me towards something that is really important to me – dealing with ideas of resource extraction and the environment and animal welfare and things specific to Alberta. A lot of the context here is visible and just so extreme…I can't think of another word. I was laughing when you said, should I be grateful, but it's so bad that there's no way you cannot respond, and you cannot work and fight against it. So there's something really important about that relationship to Alberta because it brings those issues, which are everywhere really, to the forefront.

Rita McKeough, Alternator, 2012, parking lot performance with sound. Miniature pumpjacks with DC motors, automobile parts, a 45-gallon oil drum, and a hand-cranked electricity generator built into a steering wheel. Oh Canada! MassMoCA, Boston. Technical Assistance: Robyn Moody, Audio: Richard Brown. Courtesy of the artist.

Image description: A photograph of a parking lot with two people across from each other; one is crouching down on one knee, the other is sitting on the driver’s side of a car seat that has been removed from a vehicle, and their hand is on a steering wheel that has also been removed from a vehicle. The car seats and steering wheel are sitting directly on the pavement. Rita is on the left wearing a blue jumpsuit with yellow reflective strips and a red construction worker hat. There are miniature pumpjacks and cables in the foreground and background. Part of a large red oil barrel can be seen behind the car seats. There are cars parked in the parking lot in the background.

Alana:

I was thinking about this question for myself for a long time since I moved here because it shifted my practice in many ways for the reasons you are sharing as well. But one of the things I was thinking about, and maybe this is not true, I wonder why more artists in Alberta aren't making work that specifically responds to, say, resource extraction of oil and gas. Not that there aren't artists doing this work, but even hearing you both speak to this question, I’m thinking more about the urgent need to respond. Even teaching students, it's not a usual thing that they take up as a topic. And so, I don't know. It's just a question I've been sitting with because the why (or why not) is an interesting question for me. What is it about? Is it just so accepted and normalized here that people don't think they need to respond to it or don't know how?

Christina:

I think it's so complicated. Rita, part of the reason why I think extreme is the right word is something you mentioned about how it's just such an economic force here, and it's like that across the country, you know, Canada is just one massive extraction project. But there's something here, in particular, these boom and bust cycles that become so normalized. And there's something about that normalization that I think makes it easy to ignore, and maybe it even can become uncomfortable to try to even wrap your brain around how to address it because it's so pervasive. I think it's a really good question, Alana. I also hear your question in a way that's trying to maybe encourage something as opposed to critique it. And I think there is something important about that. There are so many things that people take for granted here about the way that Alberta is.* And maybe it's these reminders that actually the ethics of these things could be really different, and maybe we've all just kinda bought into the propaganda, quite frankly.

Rita McKeough, Veins, 2016-2018, Interactive installation with performing objects, electronics, sound and animation, Production Assistance: Ann Thrale, Rachael Chiasson, Yvonne Kustec, Alex Moon, Jude Major, Bill Hornichek, Lowell Smith, Angela Bedard, and Trevor Mercer. “Veins,” Oboro, 2018. Photo: Paul Litherland, courtesy of the artist/Oboro.

Image Description: a photograph of a gallery space shaped like an “L” with a black strip with a dashed white line that looks like a road that stretches on a diagonal from the middle left to the right and then makes a turn towards the back wall of the gallery. The road is lined with black sandbags. Two bright circles of white are projected on the walls, each with a face obscured by a green leaf with eye and/or mouth holes like a mask. The face on the left appears to belong to a bird, with its ears sticking out from the leaf and big yellow eyes. The face on the right looks like an animal with its teeth bared. On the floor are large, flat tear-dropped shaped leaves of different colours: green, yellow, and orange. Throughout the space, there are drums made of tree stumps with branches attached for drumsticks. There are also small black pump jacks. In the foreground is a green platform shaped like a leaf with a long black snake.

Rita:

And I think that mention of the economic aspect, Christina, too, is really important because when I first moved here, a lot of people said to me, they were concerned about the oil sands, but you know, everybody and their family made their living from working there. So it's difficult to unravel the critical lens from the empathy for people working and finding jobs and things like that. And so many people are connected to it economically that it makes it more difficult to unravel.

Christina:

And more ironic, too, right? Because I feel like people who work in the industry are the first to know how fucked up it is –it's not stable. It's really harmful. It's physically demanding in ways that can be traumatizing and disabling. My mom also grew up in Alberta, and she's constantly saying, it's so hard to imagine <laugh>, but you know, for like, what is it - 70 years, there was a very strong conservative government in power, and then for four years there wasn't and then now here we are. So when there aren't these alternatives of, “Hey, this could actually be done this way,” I think it's really hard for people to even reconcile with common sense and the lived experience they have within the region. And if you start talking to people about it on the level of impact, they all agree everyone gets it, but it feels like there's no choice, I guess. Which is just so brutal.

Christina Battle, Notes to Self, Nov 5, 2020, series: 2014-ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

Video description: a close-up video of a rectangular white piece of paper with typed black text that reads “CONSERVATISM IS A DEATH CULT” in all caps close to the bottom of the paper. The background is dark, and some light reveals a textured grey and white surface that the piece of paper is sitting upright on. A siren can be heard in the background. The clicking sound of a lighter is heard as the tip of a bbq lighter lights the top right corner of the paper, and it begins to burn. The paper curls and smokes as the flame moves to the left until it goes out, burning the top half of the paper; the text remains unburnt. The paper is lit again on the bottom left, and the flame burns quicker this time, moving to the right, steadily engulfing each word until only the word death remains.

Alana:

Yeah, it is. And I think when it feels like there's no choice like that, it's hard for people to imagine these other ways of operating or being. I see the role of art and artists as important and integral.

Christina:

Yeah. One thing that maybe I feel is important to also say is that there are also a lot of direct ties between the oil and gas industry, and artistic institutions in this province. And I think that there's something about that as well that, in terms of visibility, that's playing a role even if it doesn't necessarily seem like one that's so overt. And I can imagine, especially artists that are maybe in certain earlier stages of their career, being aware of what it means to be talking about certain things and then also trying to progress as an artist here, getting opportunities, getting funding, all of these sorts of things could be impacted by that fact.

Alana:

Yeah. Almost every art [and cultural] institution in the province is probably tied to the oil and gas industry [and extractive industries] in some way.

Christina:

And tied mainly without question. I think there are probably ways to, you know, take their money and still question that fact, but many don't. Most don't.

Alana:

That's a good point. Looking at the overall projects created through Remediation Room, everyone had a different approach. But your works were, I think, more pointed in a way in responding to petro-capitalism, petro-propaganda, and extractivism. You've already touched on this in your answers about Alberta and how it's impacted and shaped your work, but can you talk about why it was important for you to respond to the Energy War Room directly? And how your strategies and process have developed or adapted over time while you're addressing these topics.

Image: Christina Battle, THE COMMUNITY IS NOT A HAPHAZARD COLLECTION OF INDIVIDUALS (instruction set image), 2021, made for Plastic Heart: Surface All The Way Through – curated by the Synthetic Collective for Art Museum @ University of Toronto [digital print on organic cotton, animated GIF, participatory project with seed packs (grass & wildflower seed, mycorrhizal fungi), instruction set, postcards, website.] Courtesy of the artist.

Image description: Bright pink text on a light pink background that reads: Impacts of the petrochemical industry are not equally distributed.

Rita:

Well, I think one thing, too, Alana; you know how much I love you and your work, and the questions you're posing are thought-provoking, and I really appreciate them. And I was thinking that, for me, it's really important to use that playfulness, that humor, what I call speculative propositions about ways we can think and act differently. But I think the key, too, is to be radical and put myself on the line somehow. And, you know, sometimes I fail at that, and sometimes I'm a little closer to successful, but that's really important to me, to always use my voice as an artist to examine things and try to find complexity and reveal something about it that is perhaps useful or meaningful in a way of thinking differently. And so I think those are key things, to be radical, to put myself on the line within the work somehow, and also that playfulness or humour. Getting together and trying to develop relationships to try to support and build community. You know, those are all the things that are important to me.

Rita McKeough, Long Haul, 2006. Performance (Tkaronto/Toronto), Motorized tree, found natural materials, sound chip circuit, light and power switches, plugs, drywall gauze tape, battery charger. Photo: Dave Kemp, courtesy of the artist.

Image description: A photograph of Rita and a small coniferous tree in a planter on wheels are crossing a crosswalk on a busy urban street. A silver car is stopped at the crosswalk with a black car behind it. There is a sidewalk and many storefronts along the street. On the far right, there is a line of phone booths where a man is smoking a cigarette, and another person can be seen starting to cross the crosswalk.

Alana:

I'm just thinking of, too, the word radical [meaning] the idea of grasping at the root of things, and I feel like both of you do that in your work. You’re able to get into these directed and specific conversations about such important issues, like petro-propaganda, like climate change, but in like these nuanced ways.

Christina:

I feel like I am sort of just echoing a lot of what Rita was talking about in my mind. I think I'm ultimately really interested in the complexity across all these things and how they're related. You know, we've talked about industry and politics and economics and all of these things, and I think your prompt, Alana, to think through propaganda was, to me, just such a generous prompt because it allows you to think about all of these things and the complexity across it. As well as the driving force behind a lot of it. And I think for me, ultimately, my work is centered around communication and sharing ideas, revealing things, like Rita was talking about. And then also transmitting information that often comes from an environmental or ecological perspective and trying to translate that in a way that's maybe more digestible or visible. And I think this directness that you're talking about is what I constantly sort of struggle with in my work too. I love this positioning of thinking about things as radical, which I completely agree with. And I think a lot of the time I spend with my work is trying to figure out the balance of directness because I think if I didn't edit myself, it would be like really hitting you over the head. It would not work at all. So there's something about that struggle that I really appreciate and love, but then also, it's always a struggle. I think because you've framed everything within this sort of thinking through propaganda it helped ease that struggle quite a lot, right? Because it's like, oh, this is what we're critiquing. And there's a lovely sense of freedom within that as well.

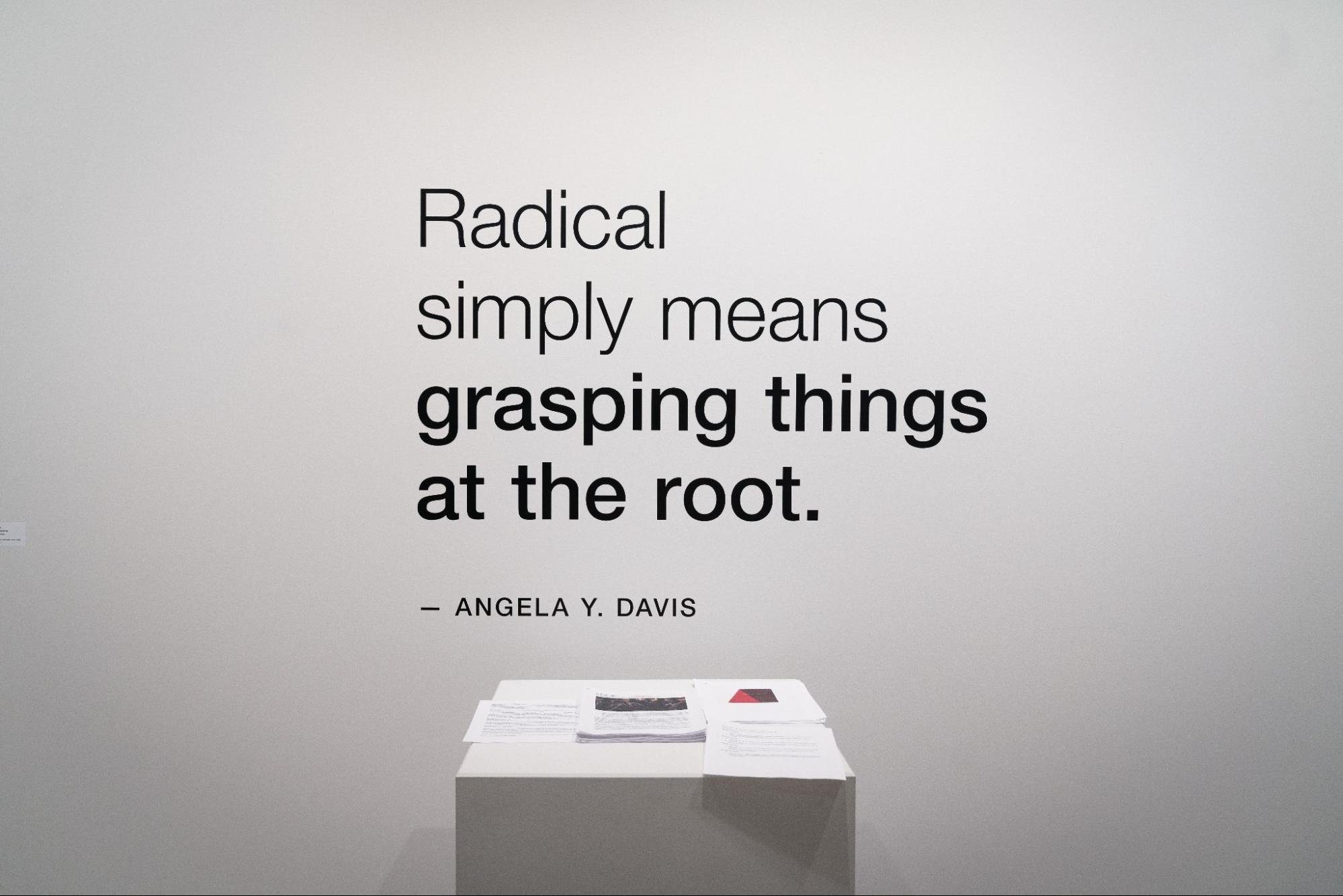

Image: Gallery entrance, Grasping at the Roots, exhibition curated by Christina Battle, with works by: Debbie Ebanks Schlums, Serena Lee, Eugenio Salas, Shawn Tse, and Scott Portingale. The Mitchell Art Gallery (Edmonton), January17 – March 28, 2020. Image by Blaine Campbell, courtesy of The Mitchell Art Gallery.

Image description: Black vinyl lettering on a white wall reads: “Radical simply means grasping things at the root - Angela Y Davis.” A plinth stands below the text with piles of paper print outs (exhibition texts and essays).

Rita:

And I loved hearing your description there, Christina, too, because when I participated in the summoning circle, the quotes and the statements on the website, but also in the exchange that we had with Alana, in our summoning circle, they were so powerful, each from a different kind of context. But bringing them all together was radical. To allow me to think with that collection of ideas was an amazing experience. And I think that is a really powerful example of what we were just talking about, unraveling things and showing their complexity. So that was a great example in the summoning circles.

Alana:

I’m thinking about how we develop ways to have these kinds of dialogues. Do we set up these [kinds of] spaces in our lives with people that we're close with or trust? How do we feel comfortable having conversations that need to be had? I'm also thinking about the role of technology and how some of these conversations are happening [or trying to take place] on social media now, but they happen in really fucked up ways a lot of the time. So it's nice to return to these in-person modes, even if they're online, like what we're doing right now. Do you have anything you'd like to share about technological shifts that might be required politically, culturally, socially, or artistically to imagine better futures? I feel like that's what we're talking about here.

Rita:

Just to start with, I mean, I might have to jump in a few times, but the one thing for me with technology is a couple of things. One thing I think is to be accountable. And I think that in using technology, like even, what you were talking about, Alana, social media, I think the key is to be accountable to what's being said and what connections and what information you're proposing and putting out there for discussion. And sometimes, what technology can do, such as interactive technologies, is it can allow actions, ideas, and relationships to be more than what we imagine them to be.

And there's also [a sense of] being more than what I was without the technology. I think there's a potential there for something very, very powerful and very positive. There's an artist, Reva Stone, an amazing artist from Winnipeg, who did an amazing piece called Carnevale 3.0 where the object, a robotic computer system, had short-term and long-term memory. It would store experiences with the viewer, then replay them for other viewers and mix them together. And everybody could respond to themselves in a different way. I think there is potential for technology to make us experience more powerful, complex, and meaningful possibilities.

Image: Christina Battle, THE COMMUNITY IS NOT A HAPHAZARD COLLECTION OF INDIVIDUALS, 2021, made for Plastic Heart: Surface All The Way Through – curated by the Synthetic Collective for Art Museum @ University of Toronto [digital print on organic cotton, animated GIF, participatory project with seed packs (grass & wildflower seed, mycorrhizal fungi), instruction set, postcards, website.] Photo: Alana Bartol.

Image description: A photograph of three kraft seed packets on the grass. Each has a different labelwith black text on a different colour, from left to right: bright blue, light yellow, and aqua green. The labels have a pattern of four interlocking hexagons, three of the hexagons are outlines and one is solid black with the text “seeds are meant to disperse”. One of the packets has been ripped open along the top.

Christina:

The first thing that comes to mind is that I think technology is one of the – yeah, I don't know how to classify it – one of the things that crosses over all of these other realms, like when you're thinking politically, economically, culturally, or socially, technology is this throughline across all of those things. And I think there's so much potential in the models of technology, something that Rita mentioned earlier about thinking about the ethics of, I think we were talking about industry. I think that's where for me, I'm really interested in thinking through technology. The ethics of the ways in which we use, invent and model different tools and how we might – because of the way those tools tend to be taken up in the society we live in – sort of rethink those models.

I think you mentioned social media too. So I think the internet is a great example of an amazing tool with so much potential. We just sort of happened to follow this particular tangent to end up with the model we are using now. And it so easily could have been different, it so easily could still be different now as well. And I’m really interested in looking to models of technology and the ways that they might be used differently. And I'm interested in thinking about that in a social, cultural, and political sense and how we might map that rethinking onto the ways that we engage with one another.

Image: Rita McKeough, darkness is as deep as the darkness is, 2020. Installation with sound, video, electronics and performance. Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Production assistance Jeremy Pavka, Ariel Ty, Alex Moon, Rachael Chiasson, Jude Major. Photos: Donald Lee, courtesy of the artist/Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity.

Image description: a large gallery space containing rows and rows of scaffold-like wooden towers topped with green sword ferns that stretch to the back of the gallery. The photograph is taken down the centre of an aisle that a visitor would walk down to view the installation.

Rita:

I think, could I add one little thing to that? I don’t know if you’ve heard of the song by Laurie Anderson called “Only an Expert.” The song is really funny, but it's talking about there being an expert on everything, every little, tiny minute nuance of everything we do, there's an expert. And that system of experts disempowers people in a way until you deem yourself as an expert <laugh> without any criteria, without any expertise. But that idea of a relationship between knowledge and technology is such an important part of that idea of knowledge. And you know, suddenly, if I come to it as an expert from a lived experience, I think you brought that up earlier, Christina, then there's a really interesting kind of new, completely different look at how we use technology. There's an opportunity there for the kinds of things we start out talking about, which is where people are proposing solutions, actions, and alternative ways to use technology, alternative ways to deal with some of the ideas of extractivism.

Alana:

Mm. Yea. I think about how the concept of the expert [as an all-knowing authority] can shut down conversations and the ability for people to have the confidence to join, fail or experiment.

Christina:

Maybe this also describes your earlier question about why is it that these issues aren't maybe taken up more in the arts in Alberta, and maybe it is that really profound – I keep just wanting to say propaganda; I'm trying to find a different word – the idea that the experts have decided how this province is gonna go and how the tar sands are gonna go and everyone just sort of thinks that that's true. We need more hijinx around the idea that the experts even know what they're talking about.

Rita:

I know, like fuck that. Yeah.

Christina:

And I'm even just thinking about the squelching of things, right? Thinking about how powerful that has been in this province, in particular, I think. Because we have these amazing institutions that are doing really awesome work within technology, within industry, within the environment, but they're just so disempowered – by design. It just needs to be revealed or better made visible or something.

Rita:

Yeah. That’s very well put.

Rita McKeough, Veins, 2016-2018, Interactive installation with performing objects, electronics, sound and animation, Production Assistance: Ann Thrale, Rachael Chiasson, Yvonne Kustec, Alex Moon, Jude Major, Bill Hornichek, Lowell Smith, Angela Bedard, and Trevor Mercer. “Veins,” Oboro, 2018. Photo: Paul Litherland, courtesy of the artist/Oboro.

Image Description: a photograph of a gallery space taken at a high angle. There is a black strip with a dashed white line that looks like a road that stretches down the centre lined with small black sandbags. A young person is walking down the road, and they are in movement and slightly blurry. There are a number of people standing or squatting on the road at the back of the gallery looking at the artwork. There are bright circles with faces projected on the walls. On the wall on the top left, the projection shows what appears to be a bird’s face obscured by a green leaf with eye holes like a mask. On the floor are large, flat tear-dropped shaped leaves of different colours: green, yellow, and orange. On either side of the road, there is a row of sculptures, the same on both sides: small black pump jacks, drums made of tree stumps with branches attached for drumsticks, and green platforms shaped like leaves, each with a long black snake on top. Black chords are running on the ground and are attached to the sculptures.

*The one thing I think about a lot is how the oil and gas industry actually only employs 6-7% of the population in Alberta - it has a big economic impact, sure (as it is across all of Canada), but it’s a lie we’ve been fed that the industry dominates our labour force. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410002301&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.10&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.2&pickMembers%5B2%5D=4.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=5.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2017&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2021&referencePeriods=20170101%2C20210101